The design geniuses who fled turmoil

How a group of émigrés overcame adversity – and enriched the world with their modernist vision. A century on from the birth of the Bauhaus school, Dominic Lutyens looks back.

By 1939, more than 300 modernist architects from and Austria – along with others from Russia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary and Romania – had settled in the UK, many of them émigrés from Nazi-controlled Europe. The more famous of these included architects Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Berthold Lubetkin and Erich Mendelsohn. Many, but not all, were Jewish refugees.

More like this:

Some re-emigrated to the US after brief stints in Britain, or moved directly to the States and to other places, including Tel Aviv. Erich Mendelsohn, a German Jewish architect, co-designed the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea in 1935 – with the Russian-born, British Serge Chermayeff – and created modernist buildings in British-controlled Palestine, including Villa Weizmann near Tel Aviv, before moving to the US.

Getty Images

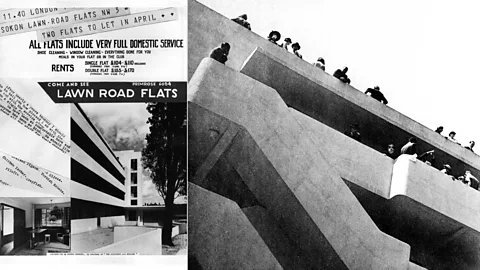

Getty ImagesAs the current UK-wide arts festival, Insiders/Outsiders highlights how these émigrés’ work greatly enriched British culture. “About two years ago I was in Hampstead, taking in how it had been a major cultural hub in the 1930s, with such modernist buildings as Lawn Road Flats, also known as the Isokon building,” says Monica Bohm-Duchen, creative director of the festival and author of an accompanying book. “I sensed a need for a wider look at the impact made by Nazi refugees on Britain. It wasn’t easy for émigrés to adapt. Anti-German feelings – dating back to World War One – as well as anti-Semitism, were rife. It was inadvisable to speak German in public. There was a book that taught Jewish people British etiquette.”

Many émigrés to the UK had been talented, experimental teachers or alumni of the highly influential Bauhaus school of art and design, founded by Gropius in 1919. This year marks the centenary of the school’s foundation, but this celebration – marked by exhibitions worldwide and a plethora of new books – should not detract from its turbulent final years.

Its promotion in the 1920s and 30s of unadorned, functionalist architecture, later dubbed the International Style, backfired as the Nazis’ power grew. Not only was the school’s cosmopolitan mix of cultures deemed anti-German, but its buildings’ flat roofs were perceived through irrational Nazi prejudice as unsuited to northern climes and therefore Jewish. In 1933, stormtroopers invaded the school and rounded up students for interrogation, forcing it to close. Gropius wasn’t Jewish but he was ostracised for his associations with the ‘degenerate’ modern art despised by the Nazis. Architectural commissions dried up and he had little choice but to emigrate.

Alamy

AlamyThe Bauhaus adhered to the principle of the Gesamstkunstwerk, meaning a complete work of art, and students there took a preliminary one-year course, called the Vorkurs, during which they became acquainted with a wide spectrum of media before specialising in one discipline. This pioneering approach provided the template for the standard foundation course in British and US art schools. On emigrating, the Bauhaus’s architects, its textile, toy and graphic designers and its ceramicists went on to disseminate Bauhaus ideals around the world.

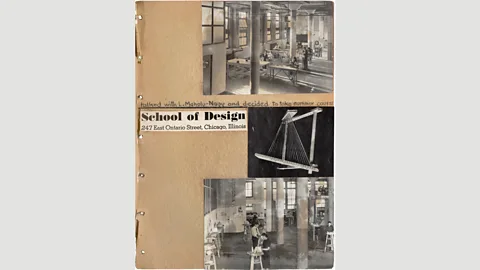

Spreading the word

“Thanks to the thorough grounding Bauhaus students received, they were more adaptable as émigrés,” says Alan Powers, author of new book Bauhaus Goes West: Modern Art and Design in Britain and America. Whether refugees from Nazi-controlled Europe could settle in a new country or not was determined by how well-connected they were, and by their ability to secure work. Gropius himself had a headstart: “His arrival to Britain was masterminded by Philip Morton Shand, an architecture critic and modernist enthusiast,” says Fiona MacCarthy, author of a new biography, Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus (Faber & Faber). “A prearranged architectural partnership was a precondition of his entry into England. He was also offered free accommodation by Jack Pritchard at Lawn Road Flats and the promise of work through Pritchard’s development firm, Isokon.”

Isokon Archive

Isokon ArchiveHampstead in north London was, like nearby Swiss Cottage and St John’s Wood, a centre for left-wing thinking, and in the 1930s several thousand German-speaking refugees, also known as the Hitler émigrés, lived there, including Sigmund Freud. The exhibition, Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain, also the title of a book by Magnus Englund and Leyla Daybelge, was recently held at The Aram Gallery in London. Today the flats are fully occupied and its ground-floor gallery has attracted more than 15,000 visitors since opening in 2014.

Isokon Plus Archive and Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia

Isokon Plus Archive and Pritchard Papers, University of East AngliaPritchard had visited the Bauhaus at its second site in Dessau in 1931 with modernist architect Wells Coates to find it closed by the Nazi-controlled council. He and his psychiatrist wife Molly commissioned Coates to design Lawn Road Flats.

Pritchard had lobbied the British government to allow in refugees from and Austria, and many came to live in this experimental building, also occupied by Hungarians Marcel Breuer, former head of the Bauhaus’s furniture department, and László Moholy-Nagy, who had run its metal workshop. Yugoslav-born Otti Berger, who had taught weaving at the school, lived in nearby Belsize Park; after returning to the Continent to look after her mother, she was arrested by the Nazis and died at Auschwitz in 1944.

Yamawaki Iwao & Michiko Archives

Yamawaki Iwao & Michiko ArchivesGropius was championed by another German émigré, Nikolaus Pevsner, who promoted Bauhaus values via his 1935 tome, Pioneers of the Modern Movement: from William Morris to Walter Gropius. Gropius, too, propagated modernist ideas with his book The New Architecture and the Bauhaus of 1935. Its avant-garde jacket, designed by Moholy-Nagy, pictured a measuring device and diagonal, scarlet sans-serif typeface.

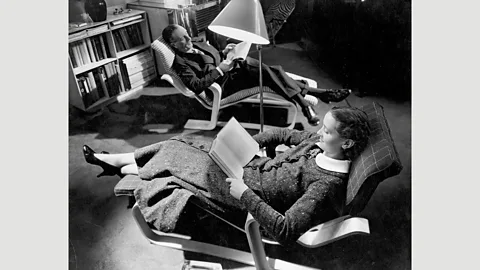

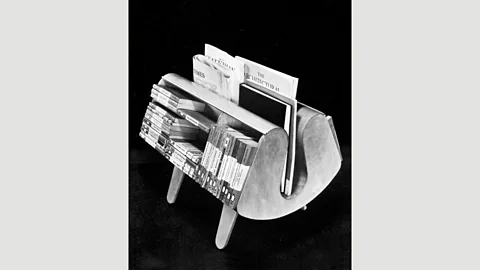

Moholy-Nagy worked for menswear shop Simpsons in Piccadilly, overseeing its displays that comprised bent plywood cabinets and clean-lined pendant lights. Breuer, who was born Jewish but renounced his religion on marrying his first wife Marta Erps in 1926, relocated to London on Gropius’s suggestion in 1936. He created furniture for Pritchard’s design company Isokon – his curvilinear plywood pieces, produced when tubular-steel furniture had become a cliché, chimed with a more romantic, organic take on modernism that prevailed in the 1930s. Pritchard also enlisted Austrian-born Egon Riss, another resident of Lawn Road Flats, to design pieces for Isokon, including the plywood Donkey storage unit for books, magazines, bottles and glasses.

Isokon Plus

Isokon PlusOne of Gropius’s UK commissions – Impington Village College in Cambridgeshire, co-designed with Maxwell Fry – echoed this sensibility of a softer modernism with its use of local brick. Pevsner lauded it as “one of the best buildings of its date in England.”

However, Gropius found his spell in Britain disappointing. “The main reason for this was lack of work,” MacCarthy tells BBC Designed. Britain at the time wasn’t receptive to modernist architecture, she adds: “Anthony Blunt rightly gave the reason for the English dislike of modernist buildings as being ‘because they’re not homey’.” In 1936, Gropius accepted an offer to become chair of the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, which had shown a great interest in the Bauhaus while it was still active.

In 1937, Gropius was given a lavish send-off – a dinner at the Trocadero, Piccadilly attended by 136 guests, among them HG Wells and furniture designer Gordon Russell – an indication of the esteem in which he was held.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn some ways it was easier for Bauhaus émigrés to settle in the US than in the UK because America had taken an interest in the school earlier – since the 1920s. By contrast, in the UK, despite the efforts of Pritchard and others, British avant-garde culture was “still ruled by the predominantly French aesthetic promoted by Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury Group,” as MacCarthy points out.

Benjamin Blackwell/ Estate of Margaret DePatta

Benjamin Blackwell/ Estate of Margaret DePattaIn the US, in 1926, the Brooklyn Museum mounted the International Exhibition of Modern Art, which included work by Bauhaus artists. In 1932, Harvard academic Alfred Barr Jr – who created the first course in the US on modern art and architecture – and colleagues Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock staged the famous International Style exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Soon after Gropius arrived in the US, he urged Breuer to follow him across the pond: “It’s fantastic here! Don’t tell the English but we are ecstatic that we have escaped the land of fog and of psychological nightmares… Here people are open and free and I believe you would have a very broad field here.” In the US, Breuer and Gropius briefly formed a business partnership, co-deg the Alan I W Frank House of 1939-1940 in Pittsburgh.

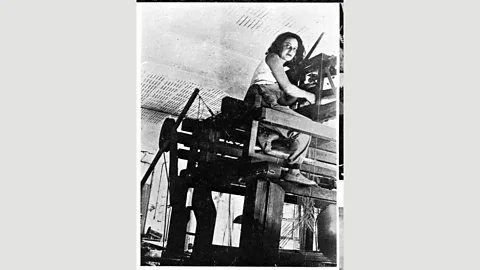

In 1933, Johnson invited Bauhaus émigrés Anni Albers, the textile designer, and her artist husband Josef to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an innovative, multidisciplinary art school founded that year. Anni Albers kept the Bauhaus teaching tradition alive in the US by having an open mind about materials: there were no looms set up at the college when she arrived, so she encouraged students to go outside and find weaving tools in nature just as ancient weavers had done. She later carved out a successful career creating fabrics for such high-profile design brands as Knoll.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1938, German-born architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – a former director of architecture at the Bauhaus – moved to the US to head up the Armour Institute in Chicago (later the Illinois Institute of Technology). He went on to establish a successful architecture practice, deg such iconic buildings as the Farnsworth House (1945-1950) outside Chicago and the Seagram Building (1954-1958) in New York.

After the war, Gropius co-designed the Pan Am building (1960-1963) in New York with Pietro Belluschi and Emery Roth & Sons. In 1964, he became involved with the Architects’ Collaborative (TAC), founded in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which perpetuated a ion for teamwork that had been initiated at the Bauhaus. “The group’s method involved all partners discussing designs in progress, with thorough consideration and criticism,” writes Powers in Bauhaus Goes West.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy now settled for good in the US, Gropius lived with his wife Ise in a house he designed in Massachusetts (built in 1938) until his death in 1969. In 1955, writing to Jack Pritchard, Ise reminisced about how living in 1930s London had benefitted them: “How immensely it helps to see places to develop a sense for the interrelationships of countries and peoples; Lawn Road Flats was our first step in this direction and remains unforgettable.” Their house in Lincoln, Massachusetts is now a museum – a homage to a genius architect and his extraordinary circle of fellow designers.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.