The cult designer who influenced a nation

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CWork by the mid-century Italian master Gio Ponti is increasingly sought after – and his designs are being recreated for a new generation.

Currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Gio Ponti (1891-1979) occupies an unusual, highly individual place in 20th-Century design history. Extraordinarily prolific throughout a career that spanned six decades – during which he mastered a dizzying spectrum of disciplines, including architecture, industrial design, ceramics, furniture and lighting – Ponti eludes easy classification.

Gio Ponti Archive

Gio Ponti ArchiveThis could be because he was mainly influenced by two seemingly incompatible styles: the Novecento Italiano – a Milanese, conservative neoclassical movement founded in the 1920s (ed by Mussolini) – and by 1930s modernism.

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CWhile this Milan-born, mid-century designer espoused the clean lines of modernism, he eschewed its typically restrained palette, embracing bold decorative effects, patterns and exuberant colour. This was evident in the florid interiors for his 1950s, futuristic, butterfly-inspired Villa Planchart, perched on a hill overlooking Caracas. Attached to its façade are additional, partially detached walls. At night, these are backlit to emphasise their contours. And Ponti adorned entire walls in his clifftop hotel Parco dei Principi (1960) in Sorrento with his ultramarine and pearlescent blue ceramic tiles made by Italian firm Ceramica d’Agostino.

Today’s Ponti’s work is coveted by collectors. At auction house Phillips’ Important Design sale last October, Ponti’s burr walnut-veneered coffee table with a grid pattern and glass top, created around 1951 for the ballroom of the ocean liner Giulio Cesare, fetched £72,500. And high-profile designers, notably India Mahdavi, who owns some of his pieces, ire his work: her plush, blush pink scheme for London restaurant Sketch has an Art Deco-meets-mid-century aesthetic that recalls Ponti’s luxurious interiors and upholstered furniture.

Gio Ponti Archive

Gio Ponti ArchivePonti was curious, open-minded and public-spirited. He was a visionary, indefatigable promoter of avant-garde design in Italy and abroad, via his magazine Domus, which he founded in 1928 and which he edited until 1940 – and again from 1948 to 1979. He also organised exhibitions at the Monza Biennial, an international architecture and industrial design exhibition, which moved to Milan in 1933, and was renamed the Milan Triennial. That year, Ponti exhibited his interior design for the ETR 200 electric train for Italian manufacturer Breda, co-created with rationalist architect Giuseppe Pagano.

Global influence

“Ponti’s versatile, inspirational career was fundamental to the establishment of the Italian identity in modern architecture and design,” says Simon Andrews, international specialist at Christie’s. “Active across all media throughout his career, Ponti revealed an individuality that defined the aesthetics of the moment. Through his editorship of Domus and of the triennial exhibitions, Ponti ed the communication of the Italian design identity to an appreciative international audience.”

This mid-century architect and designer’s heyday was the 1950s: in 1956, he co-created Milan’s slender skyscraper the Pirelli Tower, a key landmark of the city and originally seen as a symbol of the euphoric mood of Italy’s postwar economic boom, in which he played a key role. In 1957, he dreamt up his chair Superleggera, meaning super-light in Italian, for Cassina. A skeletal design with a cane seat, it is still in production. Its astonishing weightlessness was demonstrated by rather surreal photographs of children nonchalantly lifting it with one finger. Ponti considered it elemental, stripped down to its essence, describing it as “the chair-chair – devoid of adjectives.”

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CInspired by simple seating seen in the coastal town of Chiavara, Liguria, and manufactured with the aid of Cassina’s craftspeople, it embodies a key theme in Ponti’s work – the fusion of tradition with modernity, the machine-made with craft.

Gio Ponti Archive

Gio Ponti ArchiveIn 1921, the ambitious Ponti graduated in architecture from the Milan Polytechnic, married Giulia Vimercati and established a design studio with Emilio Lancia and Mino Fiocchi. In 1923, he became artistic director of ceramics manufacturer Ricardo Ginori. While his designs for the firm were neoclassical in style, he encouraged its use of high-quality mass-production.

Gio Ponti Archive

Gio Ponti ArchiveThe retrospective of this polymath’s work, entitled Tutto Ponti: Gio Ponti, Archi-Designer, is the first to be held in , where, the museum claims, his work is little-known. One of its aims is to raise awareness of Ponti’s work there. The word ‘tutto’ reflects the all-embracing scope of the show. “Our intention was that this exhibition be comprehensive, a setting in which all the varied expressions of his long creative career could come together,” says Salvatore Licitra, co-curator and Director of the Gio Ponti Archives.

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CThe exhibition is arranged chronologically in the museum’s high-ceilinged main hall – fittingly, since many of Ponti’s glamorous residential interiors boasted double-height spaces. The venue also accommodates a large-scale model of his idiosyncratic Roman Catholic cathedral in Taranto, a naval base in southern Italy, completed in 1970.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInspired by its maritime context, it illustrates Ponti’s disregard for strictly functionalist modernism: in lieu of a conventional crossing tower, it features a symbolic, sail-like structure comprising two walls perforated with vertical slits. This porous edifice was designed to blend with its natural surroundings; its interior is predominantly green, and Ponti intended creepers to grow up its walls, though this idea never materialised. He was religious but not conventionally Christian: Sophie Bouilhet-Dumas, one of the show’s co-curators, considers the cathedral open to the skies as his personal ‘pantheistic’ vision of architecture.

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CThe Ponti show incorporates a sequence of six room sets showcasing work from each decade of his career. These recreate rooms in several of his projects, including his own home on Via Dezza in Milan, with its diagonally striped walls and flexible sliding walls, where he lived with his family from 1957 onwards. They also feature designs created in collaboration with a wealth of European firms.

Gio Ponti Archive

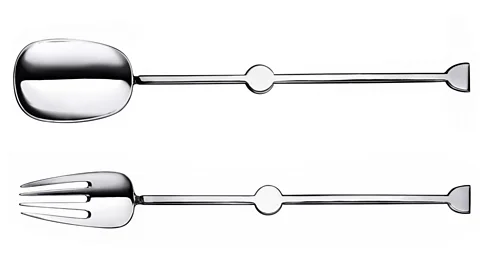

Gio Ponti ArchiveBy chance, he met Tony Bouilhet, director of French silver homeware manuacturer Christofle, while exhibiting Ricardo Ginori’s wares at the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels. Soon after they met, Bouilhet commissioned Ponti to design a villa in the suburbs Paris. Later the designer created cutlery and candlesticks for Christofle, and then the angular Aero teapot. In the 1960s he produced furniture for Knoll and lighting for Artemide.

Gio Ponti x Molteni&C

Gio Ponti x Molteni&CTestament to his growing popularity today is Italian brand Molteni&C’s limited-edition, faithfully reproduced Ponti pieces, which are part of its Heritage collection. These include the monumental D.8591 table, seating up to 10 people, originally designed for the auditiorium of the Time & Life building in New York in 1958.