The disappearing trades of rural enclaves

Julian Earle

Julian EarleTraditional trades have flourished in small villages for years. Now that youth are leaving, if elderly practitioners can’t find successors, are these professions destined to die out?

Tom Bateman

Tom BatemanFew places are experiencing the effects of population change like small villages across the world. As birth rates decline globally, young people are becoming an increasingly rare sight in rural areas – and those who are born in small enclaves often leave for professional and cultural opportunities elsewhere.

The exodus of young people means that villages are left without a next generation to whom they can along traditions, including trades.

Of course, ageing populations aren’t the only reason some trades and traditions are disappearing. New technology has provided convenient replacements for some, while restrictive government regulations have impeded others. Some older trades, conversely, have been rejuvenated by social media interest.

Ultimately, though, family businesses can’t survive in remote outposts when potential successors either don’t want to take over – or, in some cases, don’t exist at all.

Fujii Yuko

Fujii YukoNaota Seki, 91, lives in Kawaba village in Gunma prefecture, central Japan. His parents taught him to make brooms when he was a child, using broomcorn – a type of cereal grain known for its stiff stems – that the family planted themselves.

“This area is the origin of broom-making in Gunma prefecture,” says Seki via translator Yuko Fujii. Winters there were long and snowy, and families ed their time by making their own household items. As Seki grew up he turned his broom-making knowledge into a profession by learning from other artisans.

Although some younger people in Seki’s village have toyed with the idea of learning traditional broom making, none have been serious enough for Seki to his skills along to. Decades ago a young woman came from another village to learn from Seki, but though she seemed very invested in the craft, it’s unclear whether she’s carried on as an artisan broom maker.

Fujii Yuko

Fujii YukoIn rapidly ageing Japan, more than 44% of the residents in Kawaba are 65 or older. Fujii, who represents the region’s tourism division, says that a similar demographic holds across multiple villages in Gunma prefecture.

Fujii knows of other artisans like Seki in these villages who also “have no successor” to their crafts. In Ueno village, for instance, Masataka Imai is among the last to make vessels by hollowing out wood on a turning lathe.

Neighbouring Nanmoku is in a similar situation: it’s experiencing such rapid decline that it’s been called the “disappearing village.” The village’s student population went from 1,200 to 24 over the past 50 years, and 61% of its residents are now 65 or older. This is a dramatic reflection of an overall labour shortage in Japan, where the decreasing number of young people leaves many available jobs empty.

Fujii Yuko

Fujii YukoIt’s not the easiest thing to teach, how to make brooms. Because [Seki] has been making brooms for such a long time ... it might look easy, but for a new person learning how to make brooms, it’s so difficult to teach how to do it – Yuko Fujii

Julian Earle

Julian EarleDavid Boyd, 70, grew up in the fishing village of Tizzard’s Harbour in Newfoundland, Canada. A life-long fisherman, he began with cod fishing alongside his father in the 1950s. Now a short distance north-east in the town of Twillingate, Boyd is among a declining population who can professionally engage in ‘cod jigging’: a process that involves throwing a metal lure into the ocean and pulling it up quickly – a ‘jig’ – over and over again.

Boyd runs the Prime Berth Twillingate Fishery & Heritage Centre where he both works as a fisherman and archivist. The centre showcases restored traps, old boat engines and other ‘fishing artefacts’ in an effort to preserve the area’s fishing culture.

But Boyd preserves Newfoundland’s fishing culture out of more than just pride. He’s afraid the province is in danger of losing it entirely. “The demographic of the fishing industry is very much leaning toward old age pensioners,” says Boyd. “So unless 60- or 70-year-olds are having babies, there’s not many kids being born into fishing villages.”

Julian Earle

Julian EarleReasons for population decline in small Newfoundland towns date back years. In the 1950s the province government established an incentivised resettlement programme for residents of isolated rural communities to move to more populated areas, as it became increasingly difficult to deliver resources to the remote and ever-shrinking villages. Some 30,000 Newfoundlanders relocated from small fishing villages to more populous places – and some out of Canada entirely.

Now the remaining population is skewing older. Canada is rapidly ageing, which particularly threatens small enclaves: researchers for a 2017 study from Newfoundland’s Memorial University predicted that by 2036, Newfoundland will have 17% fewer residents and an average age of 50. Multiple towns are set to shrink by 30%, including Twillingate.

Boyd says that industry regulations and costs around licencing are also making it tough for young people to take the helm at fisheries. “My son is qualified to take a super-tanker from the Persian Gulf to Japan,” he says, “but he’s not qualified for me to my fishing licence along to him to put out a few lobster traps.”

Julian Earle

Julian EarleWe’ve got fishing villages now with just one fisherman, and we’ve got fishing villages now with no fishermen. We are going to reach a point, as it keeps going, where there’s going to be villages where it’s not going to be worthwhile for the fishing companies to even come and set up to buy the product – David Boyd

Tom Bateman

Tom BatemanRiitta Niiranen, 53, worked on a family-run dairy farm in the village of Pulkonkoski, in central Finland, for about 30 years. Her ex-husband’s parents owned the farm for two decades before that.

Running a family farm with 40 cows is a lifestyle, entailing around-the-clock maintenance such as cooking, cleaning and field work. “There’s a morning milking and an afternoon milking, about four hours each,” says Niiranen via her niece and translator, Hanan Mahbouba.

Niiranen no longer lives on the farm, but her two youngest sons, aged 20 and 16, express interest in taking it over one day. However it will be unrealistic for them to run the family farm alone; like many other formerly single-family owned farms, they aim to combine with a neighbouring family’s farm to divide up both the work and costs.

Meanwhile Niiranen’s 50-year-old brother has shut down his own family’s 20-cow dairy farm – his sons weren’t interested in keeping it going.

Tom Bateman

Tom BatemanDespite the steep decline in these small family-owned farms, the amount of dairy production in Finland has stayed the same. That’s because it’s now concentrated in larger farms, operations which generally have multiple shareholders and hire outside the family unit.

“Before, if let’s say there were 20 farms in a village with 10 to 15 cows each, now there’s one farm with 120 cows,” says Niiranen.

The decline in single-family farms is bolstered by the residents of small Finnish villages ageing. A 2019 study from Finnish firm Consultancy for Regional Development noted that rural populations will continue to decline as only three cities in Finland are expected to grow, including Helsinki. Another study projects the population of people younger than 15 in the country will decline to just 760,000 by 2030 (out of around 5.6 million total).

Tom Bateman

Tom BatemanYoung people don't want to stay. They want to go to the cities where there's more amusement, more other jobs. They don’t want to be tied to the farms because it’s not popular to work on a farm anymore. You're super restricted – it’s hard to leave because of all that work – Riitta Niiranen

Bernadette Young

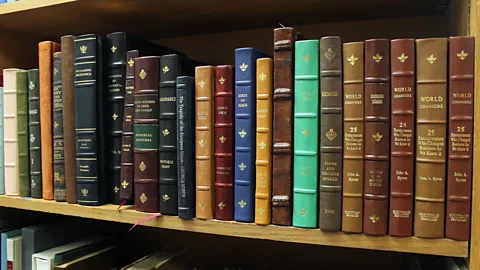

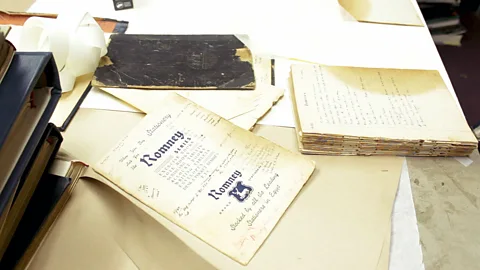

Bernadette YoungAt least a few young people are helping traditional professions survive their ageing proprietors. Among them is Julia Landau, 33, who’s taken over her late father’s 25-year-old book binding business in New York City.

Landau was never directly involved in the business, but when her father died in October 2018, she moved with her family from Brazil to take the helm of Fine Binding. Her husband, 38, is now also learning the craft with the company’s head binder.

Almost every part of the binding job is done in-house, and “we can repair any type of book,” says Landau, like decades-old children’s books falling apart at the seams and old academic journals dating back to the 1920s.

It’s not always simple to keep Fine Binding running. For instance, only one company in the city provides the service she needs to sharpen their “guillotine”-like paper-cutter. Still, it’s a pleasure for Landau to be able to keep her father’s company alive – especially in a large city where convenience and speed are paramount.

Bernadette Young

Bernadette YoungSince taking over Landau has made moves to rejuvenate the shop, like setting up an Instagram to record and share their work.

If Landau is able to capture a younger demographic with her old-school business, she may be in luck: unlike other remote villages, the population of New York City isn’t notably ageing. Baruch College data from 2016 showed that people between the ages of 25 to 29 and 30 to 34 are the two most robust populations in the city.

In other words, there may be plenty of young people to take over crafts practiced by older generations – and plenty to consume them too.Today, people of all ages come into Fine Binding, including young couples commemorating their relationships. In August the company put together a book of a couple’s text messages from when they were dating long-distance. “It’s about five inches thick,” says Landau.

Bernadette Young

Bernadette YoungI see that reflected in Instagram ... young people who are gravitating back toward, or rescuing, or embracing artisan handcrafted trades of all kinds – Julia Landau