The hidden ways that faces shape politics

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA candidate’s appearance can influence votes more than you think – so what exactly is a good look for a politician?

The face of US political power

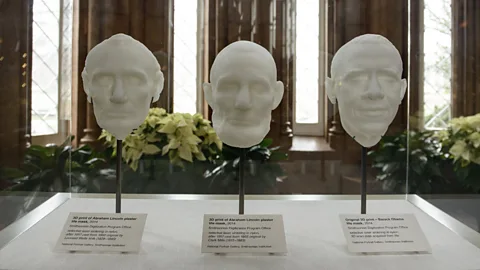

To find out what the average American politician looks like, BBC Future commissioned a composite face, which is a blend of all US Senators and House representatives. Click here to discover what it looks like, and what it says political representation in 2017.

George Washington knew it. He was particularly conscious of his forehead, which he believed would look better if it was even bigger. For maximum emphasis he’d pull his hair back into a tight ponytail – then finish the powerful, masculine look with ringlets of curls and a ribbon.

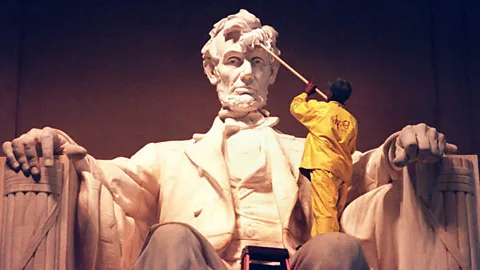

Abraham Lincoln knew it too. The public delighted in mocking his face, which was unusually angular and asymmetric. Though he’s ed as one of America’s greatest presidents, at the time he was deeply unpopular. He was as ugly as a scarecrow, they said. He was ungainly and cadaverous, they said. Eventually even the man who sculpted his likeness at Mount Rushmore ed in, saying his face was “primitive” and “unfurnished”.

We tell ourselves that what we really want from our politicians is competence, a dash of charisma and a bucket load of sensible ideas. But that might be a tad optimistic. Evidence suggests that the facial appearance of a politician significantly shapes voting decisions – and we often may not even realise it is happening.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPsychologists have known for years that first impressions play a far bigger role in our lives than we’d like to think. For example, we can’t help suspecting that those with doe eyes and pudgy lips are trustworthy souls, while those with wider faces have a tendency for aggression.

The judgements are involuntary, unconscious and happen at frightening speed: some are made in as little as 33 thousandths of a second, which is barely enough time to what you’re looking at. “In our studies people say ‘this is ridiculous, I barely saw that was a face’,” says Alexander Todorov, a psychologist from the Princeton University and leading expert in the subject.

These “thin slice” character judgements are based on the slimmest of clues. And yet they have far-reaching implications, from where you work to who you marry. Naturally, we expect CEOs and military personnel to look dominant, while those in caring professions should be baby-faced.

If you’re born with the right aesthetic, you’re more likely to be hired in the first place and may find it easier to rise through the ranks. On the other hand the wrong face – such as one that looks serious if you’re dating or stereotypically criminal in court – could blight your romantic prospects or even land you in jail.

But perhaps the most uneasy finding of all is how these snap judgements and prejudices shape politics. The science is not quite 40 years old, but the sheer weight of evidence is overwhelming. Though voters tend to have rational ideas about what makes a good leader – “The characteristic that always wins is competence,” says Todorov – the way these qualities are assessed is spectacularly reckless. In the end we discern it from the candidate’s face.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe effect is so powerful, psychologists have correctly predicted the outcome of elections in the US, Bulgaria, , Australia, Mexico, Finland and Japan, and the share of votes in US Senate, House of Representatives and gubernatorial elections using this characteristic alone.

For these studies, participants weren’t told anything about the candidates – just shown a photograph of their head and shoulders and asked to rate their competence. The method can even be used to predict the results of elections in foreign countries – and works whether you ask 90-year-olds or five-year-old children.

“There are a lot of great candidates out there who have a much lower chance of being elected because of their appearance. It’s probably not good for democracy,” says Gabriel Lenz, a political scientist from the University of California, Berkeley. How has this happened? Should we be worried? And what can we do about it?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe idea that facial appearance can influence how a population sees its leaders actually dates back thousands of years. In ancient times it was called the art of “physiognomy”, the belief that a person’s character can be judged from their face.

In Eastern cultures it was taken very seriously indeed. One Chinese king, Jianzi of Zhao, believed the face was as good a way as any to assess his grown sons as potential heirs. In particular, a noble pair of earlobes was considered auspicious. Historical documents from China boast of emperors with lobes so long, they dangled down to brush their shoulders. The preference even made its way into religious iconography: statues of Buddha are depicted with drooping lobes to this day.

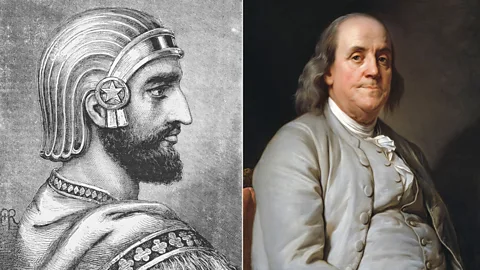

The Persians were more into noses. It began with the founder of the Achaemenian Empire, Cyrus the Great. His notable nose was long, curved and sharp, and set the royal standard for generations. Honours were only bestowed upon those with the curved, beak-y kind and young men would pinch theirs with bandages in the hope of coaxing it to grow that way.

Getty Images/Alamy

Getty Images/AlamyBy the 18th Century, physiognomy had become something of a pseudoscience. The Swiss pastor Johann Lavater analysed thousands of faces to narrow down the features that were linked to certain dispositions. In his bestselling book, Physiognomischen Fragmente, he laid out a hundred systematic rules, many of which would later be disproven. Suddenly workers, neighbours and politicians could be favoured or rejected not just on their social class and wealth, but their facial features too.

Across the globe, looking presidential became crucial to being taken seriously. Portraits of president George Washington were altered to enhance the arch of his forehead, while artists lamented not preserving Benjamin Franklin’s corpse for public view – the masses really needed to see his exemplary physiognomy for themselves.

Today’s politicians are no less image conscious. In Washington DC, business for plastic surgeons and dermatologists is booming; this is a place where faces seem to wrinkle at an unnaturally slow pace. It’s even been used as a political weapon. Back in 2004, Ukrainian presidential candidate Victor Yushchenko developed chloracne, pustules and lesions associated with over-exposure to the toxic chemical dioxin. Tests revealed the level in his blood was 6,000 times above normal; he alleged that he had been poisoned.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile these modern politicians might not be using debunked physiognomy to guide them, they are probably right to be image-conscious. Though our first impressions are usually wrong, we almost always agree on them. “There’s something very reliable about these judgements,” says Jon Freeman, a psychologist at New York University. “They’re consistent across thousands of people.”

The bias favours politicians who appear competent, but also reliable, older, attractive and familiar. In an election, candidates with this countenance tend to win with a wider margin of victory. Many of these features are self-explanatory, but what exactly a competent face looks like exactly is harder to pin down.

“In an ideal world you would randomly assign some candidates to have plastic surgery and go from there,” says Lenz. However, a slightly less invasive way to look for clues is to make one artificially. Back in 2010, together with Christopher Olivola from Carnegie Mellon University, Todorov did exactly that. The plan was to create a batch of extremely-competent looking faces and see what kind of features they ended up with.

To set up the experiment, first they taught a computer what a strong leader looks like by randomly generating faces and asking volunteers to rate how able they looked. Then they used this knowledge to create a range of faces, some of which had been enhanced to look hyper-competent.

As the attribute increased, they underwent a radical transformation: the gap between the eyebrows and the eyes shrank, faces became less round, cheekbones became more pronounced, and jaws became more angular. The competent faces were the most attractive, mature and masculine. “It’s a bit disturbing because you can see that it’s gender biased. It’s essentially a male face that people want. The face which is incompetent is a female face,” says Todorov.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAre these preferences hardwired from birth – or are they learnt? It’s a mystery that has been hotly debated for years, partly because it’s very difficult to study. It’s not like scientists can lock babies away from the outside world and ask them what kind of leaders they prefer when they grow up – though similar experiments have been performed in monkeys. A consensus is emerging, however.

“I tend to favour a more cultural association,” says Freeman. He’s spent years studying snap judgements and the hidden ways they lead to sexism in politics. “I think there’s much more evidence that our ideas about gender and competence reflect perceptions embedded in our culture.”

Take the 115th United States Congress. As BBC Future has discovered, blending together photographs of every single member yields a face that’s good-looking, middle-aged and distinctly masculine. This depressing finding makes a lot of sense when you consider that the current government is 80% male and getting on a bit; the average age is 57.8 years for of the House and 61.8 for Senators.

Globally, there are just nine heads of state under 40 and 15 female heads of government or state. No wonder this isn’t how we view competent leaders.

Which brings us to the good news. If our perceptions are learned, they’re likely reversible. “The more women you have in successful leadership positions, the UK being a good example, the more people might change their minds,” says Todorov.

The ground is gradually shifting. Over half of current woman world leaders are the first in the history of that country. And some cultures are way ahead. As of January 2017, Rwanda had the highest number of women parliamentarians, who hold 63.8% of seats in the lower house.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe US government is gradually getting older and Donald Trump was the oldest president when he entered office, at 70 years old. But elsewhere, the public are waking up to the potential of fresh-faced 30-somethings. French President Emmanuel Macron is just 39, while Austria recently elected Europe’s youngest leader, Sebastian Kurz, who is just 31.

Some biases are harder to get away from, however. In psychological circles it’s a well-known fact that people tend to develop a liking for things, such as their own face, merely because they are familiar with them. This “mere-exposure-effect” is a potent secret force in everyday life – the very reason companies pour billions into branding and songs become more catchy the hundredth time you hear them.

For a study in the journal Political Psychology, psychologists from Stanford University tried a sneaky experiment. In the run-up to the 2006 Florida gubernatorial election, they conducted a mock election by showing undergraduates photographs of the running candidates and asking who they’d vote for. But the images had been manipulated – they were actually a blend, a 60:40 mashup of the candidates and the unknowing students themselves. Naturally, the students much preferred those who resembled them.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s notoriously difficult to win an election as an outsider, especially if you’re challenging the incumbent. And since they tend to have the most familiar faces, the bias makes it even harder. Television and other visual media may be making it worse.

Today the average American watches a whopping five hours of television every day. In the build-up to the US presidential poll in 2016, well-meaning voters sat through 110 million hours of politics on YouTube alone and a record 84 million people tuned in to watch the first presidential debate. This unprecedented exposure to our politicians may be having some insidious side-effects, from supercharging the familiarity bias to clouding our judgement of presidential debates.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s thought to have been happening since the very first televised debates in the 1960s. As more and more people bought televisions, the margin of victory for incumbents widened.

Besides the familiarity effect, politicians with the most compelling faces are known to benefit disproportionately from television coverage, especially among the least educated voters. “Even if the public try to avoid politics they can’t help being affected,” says Lenz, who co-authored the study.

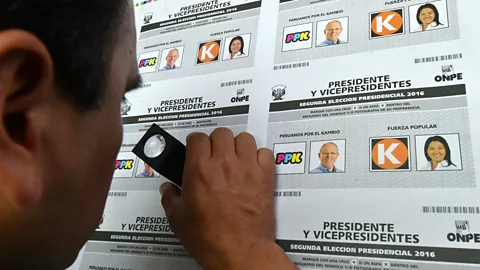

Todorov describes first impressions of faces as mental shortcuts that help us to make decisions rapidly. The key to fighting back lies in making it easier to learn about the candidates, so that voters can replace shallow decisions with rational ones, and avoiding practices that actively encourage a reliance of snap-judgements. “In some countries they put photographs of the candidates next to their names on the ballot paper,” says Lenz.

Limiting the influence of face-ism in politics is no easy task, but doing so will be a powerful step towards a greater diversity in government and ultimately, a more democratic society. Now that’s something that George Washington can really be proud of. That, and his enormous forehead.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.