The real truth about whether our tongues have 'taste zones'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor years, we were taught that the different taste receptors clump together in zones on our tongues. But it turns out that’s not quite the truth…

You probably the diagram from school – a pink tongue with different regions marked for different tastes – bitter across the back, sweet across the front, salty at sides near the front and sour at the sides towards the back. I can a biology class where we made sugar and salt solutions and pipetted them onto different parts of our tongues to confirm the map was right.

At the time it all seemed to make sense, but it turns out it’s not quite this simple.

The famous tongue diagram has appeared in hundreds of textbooks over the decades. It’s sometimes blamed on a dissertation from 1901 written by a German scientist called David Pauli Hänig. By dripping salty, sweet, sour and bitter samples onto different parts of people’s tongues, he discovered that the sensitivity of taste buds varies in different areas of the tongue.

He found the tip and the edges to be the most sensitive, but he didn’t claim that this depended on taste. Yet when he transferred this information to a graph, the impression was given that different areas corresponded to different tastes.

Steven Munger who’s a leading taste scientist from the University of Florida believes the map came from an interpretation of the graph by a psychologist with the marvellous name Edwin Boring.

Alamy

AlamyBoring conducted a number of studies which were far from dull. One of my favourite references is Boring and Boring (1917) where Edwin Boring and his wife woke people up at random intervals during the night to see if they could guess what time it was. They don’t tell us how they got people to agree to take part, but they do say that, although not everyone could do it, most people got the answer right to within 15 minutes.

Edwin Boring also wrote a book about perception and the senses which included a plan of the tongue indicating different regions for different tastes, a diagram just like the maps you sometimes still see in books today.

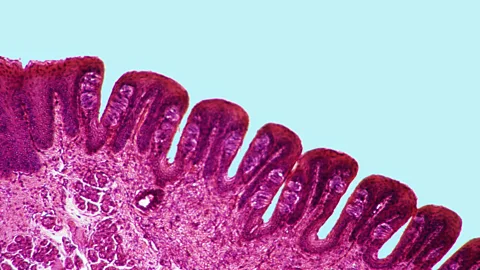

Today we know that different regions of the tongue can detect sweet, sour, bitter and salty. Taste buds are found elsewhere too – in the roof of the mouth and even in the throat. As well as detecting the four main tastes, each taste bud can also detect the most recently discovered taste, umami – the taste that makes savoury foods like parmesan so more-ish.

These tastes are not all detected in the same way. For a long time it was assumed that the receptor cells inside our taste buds could spot any taste, but this idea was overturned by Charles Zuker who runs a lab at the University of California, San Diego. Over the years he and his team identified different receptor cells for sweet, sour, bitter and umami and just one taste – salty – was preventing them from completing the set. But in 2010 they succeeded in identifying that receptor too.

We have approximately 8,000 taste buds and each contains a mixture of receptor cells, allowing them to taste any of our five tastes.

Alamy

AlamyMessages about taste are sent to the brain via two cranial nerves – one at the back of the tongue and one at the front. As a further counter to the idea that different parts of the tongue detected different tastes, it was shown that even if the front nerve, the chorda tympani, is anaesthetised, people can still taste sweetness, which in the traditional tongue map is found at the tip of the tongue.

The next mystery has been how the brain decodes these messages delivered via the cranial nerves. In 2015 a team at Columbia University found that mice have specialist brain cells which respond to each taste.

So it is true that we have specialist equipment for each taste. But rather than being clusters of taste buds in particular regions of the tongue, they are specialist receptor cells with matching neurons in the brain, each attuned to a particular taste.

Different areas of the tongue can taste anything, but although some regions are slightly more sensitive to certain tastes, those differences, in Steven Munger’s words are “minute”.

--

Disclaimer

All content within this column is provided for general information only, and should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of your own doctor or any other health care professional. The BBC is not responsible or liable for any diagnosis made by a based on the content of this site. The BBC is not liable for the contents of any external internet sites listed, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned or advised on any of the sites. Always consult your own GP if you're in any way concerned about your health.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.