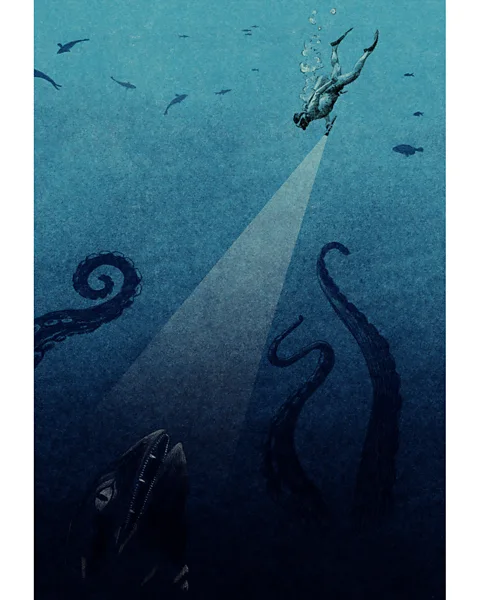

The unknown giants of the deep oceans

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel LafontExpeditions to the depths of the oceans have revealed strange dark worlds bristling with species new to science – now the race is on to discover them.

If the Earth's oceans were the size of the island of Manhattan, then oceanographer and deep-sea explorer Edith Widder estimates that we've explored the equivalent of perhaps one block – but only at first-floor level.

Oceans make up roughly 99.5% of the planet's habitats by volume, and within those largely unexplored depths there are thought to be scores of large marine animals unknown to science. When you consider smaller animals too, the number of unknown species rises to the millions.

From 13m-long (43ft) voracious carnivorous squid, to scuttling Yeti crabs huddling near hydrothermal vents, to tusked whales dwelling thousands of feet down to avoid predatory orcas, sizeable marine animals new to science are still being documented every year.

The race to try to find the remaining species is growing urgent. As deep-sea mining threatens to encroach on previously untouched seafloor habitats and climate change warms and acidifies the seas, the ocean's ecosystems are on the brink of profound change. But with new methods of ocean exploration, we are getting closer than ever to discovering more of the ocean's giants.

You may also like:

After centuries of ocean exploration, how do we know that we haven't found all the sizeable ocean animals already?

There are, in fact, several ways that scientists can estimate how many unknown species there are still to be discovered, says Tammy Horton, a taxonomist and ocean biodiversity researcher at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, UK.

For instance, imagine taking one small patch of water sitting above the ocean floor a few miles out from the coast, and recording how many new species you find there. Perhaps you see a few crustaceans clinging to a seafloor boulder, several species of fish darting around, and a couple of sediment-feeders embedded in the silty seafloor. Then go back a second time and do it again, making a note of the number of species that you didn't see there before. Maybe this time a shark swims through your section of water, and you spot one or two other new creatures.

As you go on repeating this process, Horton says, you will tend find fewer and fewer new species. If you plot the number of new species you've found on a graph over time (and do "a load of statistical analysis called rarefaction", Horton adds), you will see a curve that starts out steep as you discover lots of new species, before flattening out towards the horizontal as it reaches what's called an asymptote – at this point, after many dives to inspect your patch of ocean, you have effectively described everything that lives there.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont"If you're doing that with sharks or with fish, or with mammals, you often get to the asymptote," says Horton. "They're bigger, and bigger things get found first. But when you look at sediment samples in the deep sea, or tropical gastropods – little molluscs, tiny things on coral reefs – it never does reach the asymptote. The curve is just going up."

What that tells us is that there are still countless small sediment-dwellers to discover. But in certain parts of the seas there is a greater chance of finding large animals new to science too.

"There are patterns in species discovery and they are related to size, environment, where we look more often," says Horton. "The deep sea is one place where we're finding lots more new species."

The reason for that is simply that we've not spent much time down there. When ambitious expeditions to the deep do happen, they invariably reveal extraordinary unknown worlds.

In Suruga Bay, not far from the Pacific coast of the Japanese island of Honshū, a 1.4m-long (4.6ft) slickhead fish weighing 25kg (55lb) was determined to be a new species in 2021. Most of its closest relatives are nearer 40cm (1.3ft) long, earning this slickhead the name "Yokozuna", in tribute to the highest rank in sumo wrestling.

This impressive fish was found swimming at depths of around 2,500m (8,250ft), not far from Japan's largest and most populous island – going out to remoter patches of ocean, still stranger animals may be hiding just out of sight. The problem is, there's growing evidence that we've been seeking them out in the wrong way.

Emmanuel Lafont

Emmanuel Lafont"I make the point all the time that there could be lots of animals in the ocean that we know nothing about because of the way we've been exploring," says Widder. "I spent a lot of my career diving and in submersibles, wondering how many animals there were beyond the range of my lights that could see me, but I couldn't see them."

To try to take a look at these elusive creatures, Widder took inspiration from camera traps on land, which use infrared light to take shots of hard-to-track animals such as snow leopards. The infrared cameras don't disturb the leopards, who can't see light in that part of the spectrum. But in seawater, infrared light is rapidly absorbed – so Widder had to seek an alternative.

The solution came in the form of a stoplight fish, which has an organ that emits red light under its eye. "So most [deep-sea] animals produce only blue light and see only blue light," says Widder. "But the stoplight fish is different. It can see and produce blue light, but also red light."

Curious to find out how the stoplight fish was emitting red light in a world where blue light travelled better in water and was easier to produce, Widder dissected the light organ. She found a filter covering it. "I being struck at the time that this filter required a huge amount of energy," says Widder. "This had to be really important, for some reason."

Widder took a gamble and decided to have a filter made to imitate that of the stoplight fish. But she wanted not only to test red light in the water, but to see if different patterns of light could attract predators. "I was particularly intrigued by one deep-sea jellyfish, Atolla, which is one of the more spectacular ones. It makes a pinwheel of light. And yet this is a jellyfish that has no eyes, so it's directed at somebody else. Who, and why">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });