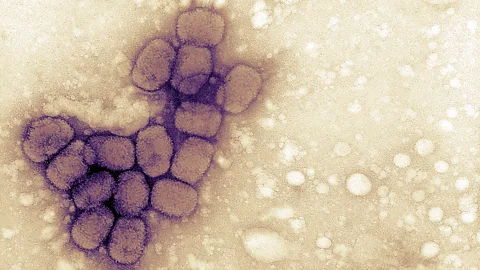

The chilling experiment which created the first vaccine

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSmallpox used to kill millions. But a chance discovery led to the first vaccine, and a transformation in human health.

Smallpox was a terrible disease.

“Your body would ache, you’d have high fever, a sore throat, headaches and difficulty breathing,” says epidemiologist René Najera, editor of the History of Vaccines website.

But that wasn’t the worst of it.

“On top of that, you’d get a horrible disfiguring rash over your entire body – pustules filled with pus on your scalp, feet, throat, even lungs – and over the course of a couple of days, they would dry out and start falling off,” says Najera.

With the rise in global trade and the spread of empires, smallpox ravaged communities around the world. Around a third of adults infected with smallpox would be expected to die, and eight out of 10 infants. In the early 18th Century, the disease is calculated to have killed some 400,000 people every year in Europe alone.

Ports were particularly vulnerable. The 1721 smallpox outbreak in the US city of Boston wiped out 8% of the population. But even if you lived, the disease had lasting effects, leaving some of the survivors blind and all of them with nasty scars.

“When the scabs fell off, they’d leave you pockmarked and disfigured – some people committed suicide rather than live with the scarring,” Najera says.

You might also like:

Treatments ranged from the useless to the bizarre (and also useless). They included placing people in hot rooms, or sometimes cold rooms, abstaining from eating melons, wrapping patients in red cloth and – according to one 17th-Century medic giving “12 bottles of small beer” to the patient every 24 hours. The intoxication might have at least dulled the pain.

There was, however, one genuine cure. Known as inoculation, or variolation, it involved taking the pus from someone suffering with smallpox and scratching it into the skin of a healthy individual. Another technique involved blowing smallpox scabs up the nose.

First practiced in Africa and Asia before being eventually brought to Europe in the 18th Century, and North America by an enslaved man named Onesimus, inoculation usually resulted in a mild case of the disease. But not always. Some people contracted full-on smallpox and all those inoculated became carriers of the disease, inadvertently ing it on to people they met. A better solution was needed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy the 1700s, it was relatively well known in rural England that a group of people seemed to be immune to smallpox. Milkmaids instead contracted a relatively mild cattle disease called cowpox, which left little scarring.

During a smallpox epidemic in the west of England in 1774, farmer Benjamin Jesty decided to try something. He scratched some pus from cowpox lesions on the udders of a cow into the skin of his wife and sons. None of them contracted smallpox.

It wasn’t, however, until many years later that anyone knew of Jesty’s work. The man credited with inventing vaccination, and more importantly, popularising it, made similar observations and came to similar conclusions.

Edward Jenner was a country doctor working in the small town of Berkeley in Gloucestershire. He had trained in London under one of the foremost surgeons of the day. Jenner’s interest in curing smallpox is thought to be influenced by his childhood experience of smallpox inoculation.

It’s said that Jenner was psychologically scarred by that experience, some of his motivation was just how horrific he'd found it,” says Owen Gower, manager of Dr Jenner’s House Museum. “He was thinking, ‘I want to find an alternative, something that's safer, that's less terrifying’.”

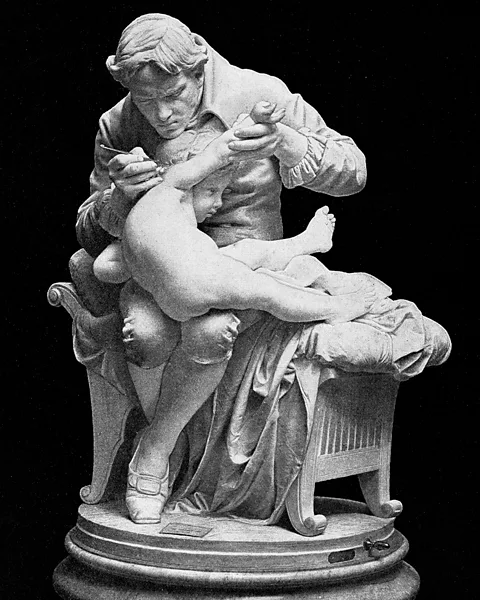

In 1796, after gathering some circumstantial evidence from farmers and milkmaids, Jenner decided to try an experiment. A potentially fatal experiment. On a child.

He took some pus from cowpox lesions on the hands of a young milkmaid, Sarah Nelms, and scratched it into the skin of eight-year old James Phipps. After a few days of mild illness, James recovered sufficiently for Jenner to inoculate the boy with matter from a smallpox blister. James did not develop smallpox, nor did any of the people he came into close with.

Although the experiment worked, by today’s standards it was ethically problematic.

Getty Images

Getty Images“It really wasn't a clinical trial and the choice of who they vaccinated really makes you uncomfortable,” says Sheila Cruickshank, professor of immunology at the University of Manchester.

Nor did Jenner know the science underlying the discovery. There was no understanding that smallpox was caused by the variola virus, and the functioning of the body’s immune system was still a mystery at the time.

“A lot of what they were doing was relying on creating immunity, creating antibodies, creating memory, and they had no concept of that,” says Cruickshank. “It's mind blowing, slightly scary as well.”

Nevertheless, Jenner realised that his smallpox vaccine – the name derived from the Latin for cowpox, vaccinia – had the potential to transform medicine and save lives. But he also knew he would only halt the disease if he could vaccinate as many people as possible.

“Jenner didn't seek to make any money from his vaccine, he wasn't interested in patenting it,” says Gower. “He just wanted people to know about it and he wanted to share it.”

He converted a rustic summerhouse in his garden into his Temple of Vaccinia and invited local people to be vaccinated after church on Sunday.

“He wrote to other physicians offering them samples of the vaccine material and encouraging them to do it themselves so that people were vaccinated by their own local trusted health professional,” Gower says. “It's a theme that we see now in of vaccine advocacy and ensuring acceptance of a vaccine is the right message delivered by the right person.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter Jenner published his findings, news of the discovery spread across Europe. And then, thanks to the of the King of Spain, around the world.

King Charles IV had lost several of his own family to smallpox, while others – including his daughter Maria Luisa – were left scarred after surviving the disease. When he heard of Jenner’s vaccine, he commissioned a physician to lead a global expedition to deliver it to the furthest reaches of the Spanish Empire. Although to be fair, most of these areas of the world were places European colonists had introduced smallpox to in the first place.

In 1803, the ship sailed for South America. On board were 22 orphans to act as vaccine carriers.

“There is no way of mass-producing vaccine, so they give it to a child,” explains Najera. “The child will develop the lesion, then they take it from their child a couple of days later, give it to the next child and so on and so forth down the line.”

The children were cared for on the journey by the orphanage director, Isabel de Zendala y Gomez, who also brought along her own son to contribute to the mission.

Dividing forces, the expedition travelled through the Caribbean, South and Central America and eventually crossed the Pacific to reach the Philippines. Within 20 years of its discovery, Jenner’s vaccine was already saving millions of lives. Soon, smallpox vaccination was common practice around the world. It was completely eradicated in 1979.

“Personally, it gives me hope for the Covid-19 vaccine,” says Najera. “Now we have 200 years of knowledge of viruses and the immune system but Jenner did all this without knowing what he was dealing with.”

“Jenner’s up there as one of my top scientific heroes,” says Gower. “His determination and innovation changed the world and saved countless millions of lives and continues to save lives.”

Richard Hollingham is a science and space journalist, feature writer for BBC Future and the author of Blood and Guts, A History of Surgery.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.