Pinocchio: The scariest children's story ever written

Netflix

NetflixGuillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is an acclaimed new film that brings out the darkness in this 150-year-old children's tale, writes Nicholas Barber.

Two major Pinocchio films premiered this year, but it isn't too difficult to tell them apart. One of them is Robert Zemeckis's live-action remake of the 1940 Walt Disney cartoon, with Tom Hanks as a cuddly Geppetto, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt providing the voice of Jiminy Cricket. The other, directed by Guillermo del Toro, has Geppetto's flesh-and-blood son being killed by a World War One bomb, Geppetto (David Bradley) carving a wooden boy in a drunken fury, and Mussolini's fascists ruling over Italy. And then there are the deaths, plural, of the title character. "Pinocchio dies in our film three or four times," del Toro tells BBC Culture, "and has a dialogue with Death, and Death teaches him that the only way you can really have a human existence is if you have death at the end of it. There are roughly 60 versions of Pinocchio on film, and I would bet hard money that that doesn't exist in any of the other 60."

More like this:

The director has even put his name in the stop-motion film's full title, Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio, which is fair enough, as it could be the quintessential Guillermo del Toro production. Its eerie magical creatures appear to be relatives of those in 2004's Hellboy, and the conflict between an unconventional protagonist (Gregory Mann) and a spiteful government official (Ron Perlman) echoes the conflict in The Shape of Water (2017). "We made it clear from the beginning that this movie was of a piece with The Devil's Backbone and Pan's Labyrinth," says del Toro, referring to two of his earlier horror fantasies, which brought together the supernatural and the Spanish Civil War. "I made it clear [to Netflix, which financed the film] that I'm not making this for kids, I'm not making it for the soccer parents. I'm making this for myself and my team."

As idiosyncratic as del Toro's vision is, though, he isn't taking a sweet fairy tale and making it horrifying. Internationally, the best-known telling of the story is still the Disney cartoon, and in that, Pinocchio was turned into a donkey and swallowed by a giant sea monster. "I saw the Disney film at a very early age," says del Toro, "and it's one of the scariest films I've ever seen."

The original book is scarier still. As del Toro says, there have been 60-odd Pinocchio films, and "even before I saw the Disney film I saw him in colouring books and picture books". But the novel stands apart from all of them as one of the strangest and most disturbing classics in children's literature.

Disney

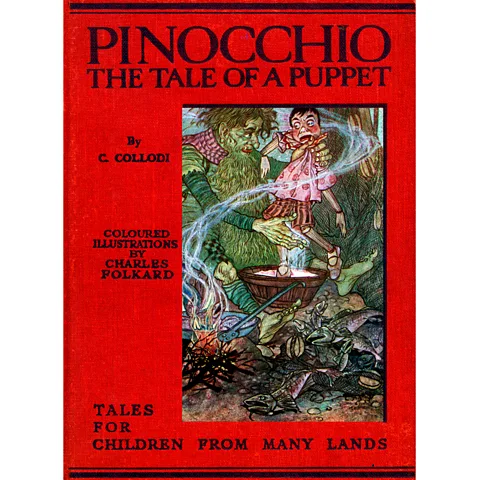

DisneyIts author is Carlo Lorenzini, who took his pseudonym, Carlo Collodi, from his mother's hometown. A civil servant, political journalist and author, he was employed by a Florentine publisher in 1875 to translate a selection of 17th-and-18th-Century French fairy tales. This volume was so successful that Collodi was asked to write more children's stories, preferably with strong moral messages. In 1881, La storia di un burattino (The story of a puppet) was published as a weekly serial in a children's newspaper.

Anyone who knows Pinocchio only from his screen incarnations should beware. Geppetto is poorer than he is in either the Disney films or the del Toro one: he has a fire painted on the wall because he can't afford the fuel for a real one. The character we know as Jiminy Cricket, or Sebastian J Cricket (Ewan McGregor) in del Toro's version, is simply the Talking Cricket. And he lasts for a grand total of two pages before Pinocchio throws a mallet at him, and "he was stuck to the wall stone dead". The Blue Fairy is a ghostly Little Girl who speaks "without moving her lips... in a faint voice that seemed to come from the other world". And the Cat and the Fox string Pinocchio up from an oak tree. "The noose, growing tighter around his neck all the time, was choking him," writes Collodi. "He could feel death approaching..."

Alamy

AlamyTo make matters even grimmer, this could have been the end of the story. Collodi had planned to leave his hapless hero dangling from the noose, and it wasn't until readers begged for further instalments that the serial was resumed four months later. The next section isn't quite as macabre: the dead Little Girl is reborn as a fairy. But it's still perplexingly weird. Why exactly does Pinocchio have a brief encounter with a giant snake that laughs itself to death?

Fear of an adult world

The book's closest counterparts in English are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking Glass. The latter was published in 1871, 10 years before Pinocchio; Lewis Carroll's tales were released as a Disney film in 1951, 11 years after Pinocchio. Ann Lawson Lucas, who translated and introduced the Oxford University Press edition of Pinocchio, its that both can be off-putting to children: "Alice's adventures can seem frightening (or irritating) and Pinocchio's misadventures tiresome (or nightmarish)," she tells BBC Culture. For adults, Collodi's increasingly bizarre narrative raises the questions of what is being satirised and symbolised, and what Collodi was saying about the newly unified (in 1871) Kingdom of Italy.

Pinocchio "has been compared to the Odyssey and to Dante's Divine Comedy," says Lucas in her introduction. "In Italy especially, as much has been written about it and as many interpretations put forward as for those great works of world literature... There have been ideological, Marxist, philosophical, anthropological, psychoanalytical and Freudian readings."

One reading even argues that Pinocchio is a Christ figure, because Geppetto is a carpenter whose name is a diminutive of Giuseppe, or Joseph, and the Blue Fairy's colour scheme matches the blue mantle traditionally worn by the Virgin Mary. Lucas rejects this interpretation, but it is echoed in Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio when the living puppet gazes at a crucifix and muses, "He's made of wood, too. Why does everyone like him, not me?"

The novel's most faithful big-screen adaptation is a spellbinding Italian film from 2019, written and directed by Matteo Garrone (Gomorrah), and featuring Roberto Benigni as Geppetto. (In 2002, Benigni played Pinocchio in a film he directed himself, even though he was 50 at the time.) For Garrone, Pinocchio is a chronicle of fatherly love, rural poverty and dusty Tuscan scenery. For the co-director of del Toro's version, Mark Gustafson, Pinocchio is "a creation story" about a work of art taking on a life of its own, separate from its creator. "As an artist," Gustafson tells BBC Culture, "you make something, you think you know what you're making, and you put it out in the world, and then maybe it doesn't get the reaction you wanted. But in a way that's a good thing. You want to shake things up. That's the ideal creation."

The overriding theme for del Toro is the unfairness of children being bossed about by adults. In Collodi's novel, Pinocchio is punished every time he is disobedient, and ultimately learns to do what he is told. "We tried to very pointedly avoid that," says del Toro. "I really wanted to make a disobedient Pinocchio, and make disobedience a virtue. I wanted everybody to change but him. As the movie progresses, the cricket learns from Pinocchio, and Pinocchio learns very little from the cricket. I was being contrarian in a way, but it was more truthful to what I felt as a kid. I felt all this domestication was daunting and scary."

Alamy

AlamyWhat unites every re-telling is Collodi's indelible images: a wooden boy; a talking cricket; a nose that gets longer when you lie. But running alongside all of those is a powerful truth. "I think it's fear of the adult world," says del Toro, "this idea that you are thrown into a world of adult values that are not only hard to understand but eventually prove false. That's how I came to feel as a kid. All the things adults told you, they didn't understand themselves." In the first half of the book, it's a few villains who cause trouble for Pinocchio. In the second half, four black rabbits carry a coffin into his room to take him away while he is still alive, and a judge (who happens to be a gorilla) throws him in jail because he is the victim of a theft. As fantastical as these episodes are, the fear they evoke, the feeling of being lost and powerless in a grown-up society where nothing makes sense, is more recognisable than the relatively orderly and logical yarns in most children's books.

The same goes for the central character. Everyone knows that Pinocchio wants to be a real boy, but a key reason why he has been so adored for almost 150 years is that he is always as real as anyone in literature. Rather than being an intrepid, noble hero, Pinocchio is rude, selfish, naive, curious, forgetful, easily swayed by temptation, slow to learn from his mistakes, upset when things go wrong, but kind, well-meaning, and capable of bravery. Wooden or not, he couldn't be much more human than that.

Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio is released on Netflix on 9 December.

Love film and TV? BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.