From Withnail and I to El Topo: What makes a cult film?

Alamy

AlamyTo launch BBC Culture’s new series on cult films, Larushka Ivan-Zadeh explores how to separate guilty pleasures from genuine underground hits.

What crazy alchemy can transform the worst movie of all time into a golden work of staggering genius? When it’s dubbed a cult classic, of course! Welcome to the cinematic universe of the second coming, where Return Of The Killer Tomatoes! is as venerated as Citizen Kane and the offbeat, experimental, queer, schlocky, flawed and downright weird is worshipped.

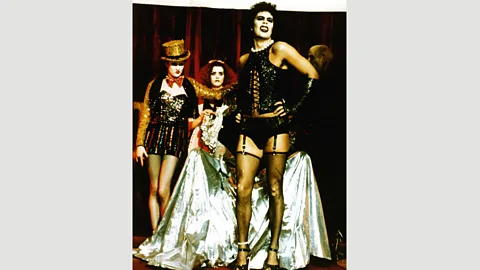

Yet smelling out a genuine classic from just another ‘bad’ or misjudged movie (hallo Cats! Though give that time…) is trickier than you might think, even for the experts, as we found when we set out to compile a new cult canon. “Every time you think about ‘cult’ and what it means, there’s always an exception to the rule,” its Michael Blyth, who programmes the annual Cult strand for the BFI’s London Film Festival alongside their LGBTQ+ festival BFI Flare. For him, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) gives the cult classic blueprint. “When it was released, it wasn’t a critical or commercial success and yet it found an audience who so fell in love with it, they got together to have this celebratory union, where they could dress up and quote along with and create a whole subculture out of this film that would otherwise have been lost or forgotten.”

Alamy

AlamyI was one such celebrant. Aged 15, I popped my Rocky Horror Picture Show live audience participation cherry at a midnight screening in London. Here I channelled my inner Transylvanian transsexual, dressed in fishnets, a borrowed tailcoat and armed with a water pistol (to simulate rain at a key moment), and chanted along to the pre-ordained responses I’d devotedly learnt from a bootleg cassette tape. It was one of the most joyful movie-going experiences of my life. Yet as the years have gone by and Rocky Horror has been absorbed into the mainstream, you wonder if even this ultimate ‘cult’ movie can honestly still be classified as one.

“We have to be careful not to overuse the word ‘cult’ so it loses all meaning,” agrees Blyth. “Some people talk of Star Wars being a ‘cult’ film because it has such a developed fandom and subculture but I think ‘cult’ should fundamentally exist in the original ways we understood it – a celebration of lowbrow culture, based around ideas of camp and irony, transgression and subversion.” And while the Star Wars universe might hold many wonders, there’s a notable lack of zombie cheerleaders or obese transvestites eating real dog poo on the Death Star (unless I missed that in the Blu-Ray extras).

ionate following

So where does the ‘original’ meaning lie? US film writer Danny Peary supposedly first gave the term currency with his 1980 book Cult Movies. In it, Peary picks out 100 films from Andy Warhol’s Bad to The Wizard Of Oz which “have elicited a fiery ion in moviegoers that exists long after their initial releases”. This alternative film canon contained such world offerings as El Topo, Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s hallucinogenic head-trip of an ‘Acid Western’, and naughty French softcore classic Emmanuelle. Even so, the term ‘cult movie’ was pretty much an “American thing” according to programmer-turned-film historian Jane Giles, author of Scala Cinema 1978-1993.

Alamy

AlamyMy top five cult classics

Director Babak Anvari’s picks

While these are all arguably acclaimed films now, they weren’t so highly regarded when they were first released…

1 – The Shining (1980)

Famous case: when The Shining came out – nobody liked it. It won two Razzies for Kubrick – can you believe that?! [Note: The Shining was actually nominated for Worst Director and Worst actress at the first ever Golden Raspberry awards]. It was only years later with home video that it became more popular because people started to rewatch it over and over and to see all the layers and start reading more and more into it. Now it’s considered one of the best horror movies ever made.

2 – Donnie Darko (2001)

I was at film school in London when it came out and I became so obsessed with it. It didn’t do well in America at all, but it became very popular in the UK. I have this book on Donnie Darko and at the beginning there is a letter that director Richard Kelly wrote thanking the British audience; because the film grew very popular here, it started getting popular in America. I think the reason it got popular here is that me and my coursemates and people my age related to it so much. That idea that there’s this crazy messed-up kid who doesn’t feel like he fits into this perfect suburban world who ends up being this schizophrenic superhero? It had everything! I actually watched it recently about two weeks ago with someone who hadn’t seen it before and I still love it.

3 – Fight Club (1999)

One of my all-time favourites as a teenager. I was so obsessed by that film and I still am. Some people today might say ‘oh, but that was a really big hit’ – but it wasn’t when it came out. Critics hated it and the audiences didn’t like it. People said it was too violent or too crazy. I was listening to a podcast with the writer recently and the studio tried to bury it and it was only at the very beginning of DVD when the special edition boxset came out and people started watching at home, that’s when people started falling in love with it and thinking ‘wow, this is great’. There’s a famous story that Rosie O’Donnell went out of her way on her TV show to make sure people did not go out and watch this film because she hated it so much. She went on air and said “I’m going to spoil the ending so you don’t go and watch this film”.

4 – Eraserhead (1977)

I watched it when I was quite young. I think I was 15 or 16. And I got so disturbed by it. I had no idea what it was about but that’s exactly why I loved it so much. It really shook me. To this day I think it’s a very influential film for me. As a young student the films that used to excite me so much were the cult films because the people making those kind of cult films were those filmmakers not following the formula. So I was like “hell yeah, I want to do something like that”; something like a Cronenberg film or a Lynch film.

5 – Pi (1998)

It was Darren Aronofsky’s very first film and he made it with almost no budget. It’s so stylised and also sort of tries to be deep and philosophical – and again, as a film student, that was like our dream. I the script for Pi was going around at our film school like it was some sacred sort of text, because Aronofsky published a copy of the script and also his diary of when he was making the film. It was kind of like one of those books you’d read as a student dreaming “this is the way that I’m going to make my first film! With no money! F**k the system!”

Giles ed The Scala as a programmer in 1988. Modelled on the midnight movie theatres of New York and LA and the queer theatres of San Francisco, The Scala was the legendary London repertory cinema which ‘Pope of Trash’ auteur John Waters once described as “a country club for criminals and lunatics and people that were high… which is a good way to see movies”. Pretty much every film The Scala screened, including one of Giles’s personal faves, a hardcore 1975 horror/comedy called Thundercrack! (still banned in the UK), could arguably be called a ‘cult’ classic, yet they generally weren’t back then. According to Giles: “Even when Withnail and I came out, which was the very definition of something that became a cult movie, it wasn’t called that.”

For Giles and her fellow acolytes, the definition of a true cult movie was one that had to be discovered and that would appeal to the Scala’s criss-crossing rainbow tribes of gay people, punks, rockabillies and goths. She considers that a big part of what made Withnail And I a cult was that it had a botched theatrical release, meaning, despite a handful of glowing critical reviews, hardly anyone could get to see the film – this being a pre-video era. “It used to be one of the benchmarks – that if something was difficult to track down it was a cult movie by definition,” says Giles. She references Ali Catterall’s book about British cult movies, Your Face Here, in which he argues that it wasn’t until the 90s and early noughties that marketeers decided ‘cult’ was a cool word and started slapping it on any and everything that wasn’t completely mainstream – to the point it became meaningless.

Changing meaning

So in 2020, an era when Netflix hands you ‘cult classics’ on an algorithmed platter, are the glory days of cult movies over? “I think that definition has really changed,” says Giles.

Alamy

Alamy“For me, cult movies are the ones that are kind of out-of-the-box,” declares rising Iranian director Babak Anvari. “You can’t fit them anywhere.” Furthermore, any definition is location dependent. He points out that growing up in Iran, pretty much every Western movie would be considered ‘cult’, because most of them were banned. “We had these video dealers that would come to your door with a briefcase full of tapes – it was kind of like buying an illegal substance! So pretty much every film that I watched in the 80s and 90s had that cultish feel, even mainstream films, like Titanic.” It’s interesting to think that somewhere in an Iranian basement there might have been a 90s underground Titanic club night full of drag queen Kate Winslets.

Anvari’s own feature debut, Under The Shadow (2016), a psychological horror set in 1980s Iran, has a cult feel, even if it’s arguably too critically garlanded to be a true ‘cult’ phenomenon. Mark Kermode recently cited it as one of his top 10 films of the last decade. As a filmmaker, did or would Anvari set out to make a cult movie? “If my films were considered ‘cult’, that would be a badge of honour!” he declares. “As a film student, those were the films that really excited me. But to make a cult film on purpose? I don’t think that’s possible.”

He’s right. Studios might try to market films as ‘cult’, but you can’t manufacture one. Because, unlike genre, a cult classic isn’t defined by the content of the work, but by its audience (be it only a devoted cult of three). In drawing up our own criteria, we have taken all this conflicting advice into . Our series will include those films that were box office or critical failures, which went on to have another life beyond their individual release.

And what’s cheering, particularly given this is written during the time of lockdown, is that cult life is a gloriously communal one. As Blyth concludes: “Cult cinema has such a way of bringing people together.” One of his fondest memories as a programmer was a sell-out screening of Troma’s 1984 B-movie The Toxic Avenger. “There was such a shared electricity of enjoyment. People who’d been watching this at home alone, feeling like they were the only one who could truly love The Toxic Avenger, but no – here they are in a room full of people who also share this weird perverse love for a movie that’s widely regarded as trash. I love that there’s something oddly empowering about that.” Long live cult cinema!

Love film and TV? BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.